Can’t Improvise Phrases That Sound Good? 5 Ways To Fix That

- Jazz Lesson Videos

- Jan 15, 2023

- 6 min read

There’s a pretty common shared experience for musicians—you learn a few chords, a few scales, a few licks, and you start improvising your own phrases. At first, it’s exciting, but after a while, you start noticing your improv doesn’t quite sound like what the pros are doing. You might be plunking out a few notes, some of them sound good, but maybe not like a coherent phrase or idea.

This is a lull that all musicians hit, and some stay here longer than others. Today we’re going to tackle five ways you can improve your improv and break out of a rut or boost your playing.

Before we get going, make sure to check out 50 Easy Major Licks PDF Package, which gives you some great examples to get you familiar with the language of phrasing. For more, you can also follow along with our video here!

While it’s cool to play complex, difficult phrases, nine times out of ten, the phrases that are short, sweet, and accessible are the ones that reach your audience.

Contents

Start short

Our first way to make a good sounding phrase is to start short.

When you think of phrases from Charlie Parker, you think of long, winding, complex phrases. And he was able to do that, and he often did do that. But many of his greatest solos were just one chorus solos—where he played a lot of phrases that only lasted a couple of bars.

And part of this likely comes from how we perceive music as language. Having a musical sentence that makes sense and has a point makes it easy to remember and repeat. It’s how things can also become earworms. Chances are that you’re not walking away from a super complex song singing the chorus after one listen, but you may be after hearing a pop song with a simple hook.

So let’s check out a phrase—this one is a bar long, 10 notes in total, with every note as a chord tone (except the 9th, which you can still consider a chord tone). It’s based on a short ii - V - I, which is a progression that comes up all the time in all sorts of tunes, especially jazz standards.

We’ll start on the third of a Cm7, then jump down to the fifth, up to the seventh, followed by the ninth. Since many guitarists and pianists will use the ninth and sixth, you can generally consider them chord tones, too.

Our next move voice leads us down into the fifth of F7. Voice leading is really simply just moving in a melodic way, using the smallest intervals for transitions between chords. By doing this, it feels natural and doesn’t feel jumpy when moving from chord to chord.

From the fifth of F7, we’ll continue with chord tones—fifth, third, root, and seventh, which voice leads stepwise down into the third of the Bbmaj7 and we hop up to the root.

This phrase is short, but memorable. What we’re seeing here, too, is that it ends very deliberately—we just have a couple snappy notes here to end the phrase.

End Deliberately

That brings us to our second component, which is ending deliberately.

So when the audience cheers or gives the “jazz woos,” it’s generally not in the middle of a phrase … it’s at the end.

So you have to make the end of your phrase sound deliberate—just as if you were giving a public speech. While the whole speech matters, the last sentence matters most of all. You have to conclude your point well, which is the same for phrases.

This next phrase will be slightly longer, a four-bar phrase, but the ending is going to be deliberate. We’ll work with a long ii - V - I, which again is good for getting versed in the language and sound of jazz. This will help you develop your own language over a ii - V - I progression, which will have a lot of use through your study of jazz.

The phrase uses almost exclusively chord tones, but since it’s longer, we have a little bit more rhythmic variation.

We’ll go from the fifth, to the third, the root, then the seventh, voice leading down into the third of the F7. Then right after going down, we’ll arpeggiate up. So from the F7, we’ll play the third, fifth, seventh, and ninth, adding a little syncopation, since we have a longer phrase. This helps break this up a bit. But we’ll still voice lead with stepwise motion down into the third of the Bbmaj7. We’ll go back up to the fifth, seventh, and ninth. We’re going to give our deliberate ending here—with the root and the sixth. The sixth on a major chord is a really nice note with a lot of color. With a little sustain, the sixth is a great melodic way to end a phrase.

For more ideas on how to end a phrase melodically, check out some of the other examples in our 50 Easy Major Licks PDF package.

Using Close Intervals

A lot of times when you hear a new or developing player, they’re just sort of pushing buttons, jumping around a scale, uncertain of the next thing they’re going to play.

These big jumps are actually what’s hurting them—a lot of times melodic lines sound best because their intervals stay very close.

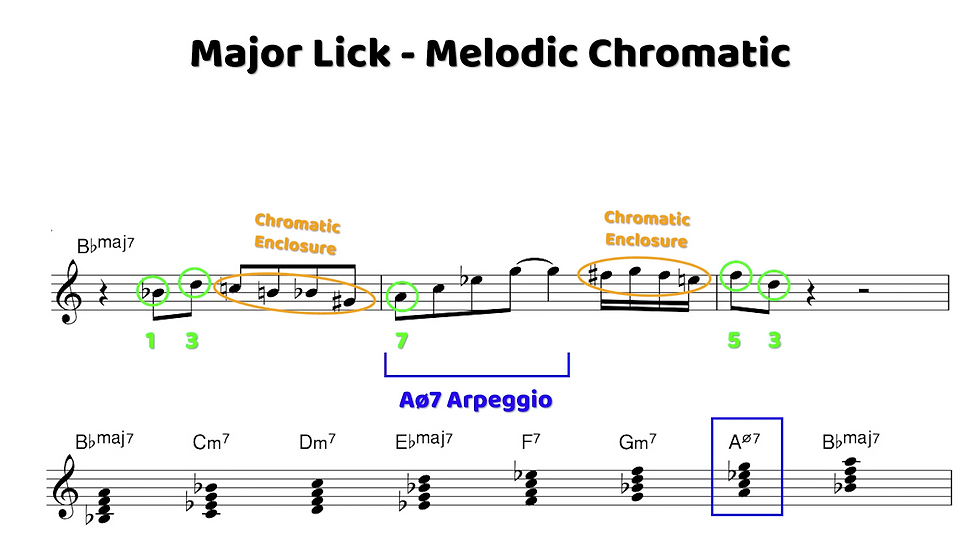

In this phrase, we have more than just chord tones. We have a good amount of chromatic approach notes, which we’ll talk a bit more about in a second.

But despite how much is going on in this phrase, you notice that it never hops more than a major third from note to note. The first few notes hit that interval exactly going from the root to the third.

That’s when we get to a chromatic enclosure. This takes a chromatic note below and a chromatic note above to outline and direct to the target tone.

People often ask how you can make something sound more interesting when you’re playing the same chord for a bit. Adding chromaticism through enclosures is a great step, but you can also use diatonic arpeggios.

In this example, we’re arpeggiating an Aø chord, which is the seventh of Bb major. So from the seventh of Bb, we build up third, fifth, and seventh for the Aø7 chord. Essentially, we’re outlining a chord that sounds nice within the other chord.

Then we have a nice rhythmic embellishment and a chromatic enclosure on the fifth, with a nice snappy ending, playing the fifth and the third.

Try Pentatonics

You can’t go wrong with the pentatonic scale. And honestly … that’s kind of the point. The pentatonic scale purposefully omits some of the stronger tones that may clash in the major (or minor) scale. It has a strong, confident sound and is a favorite for beginners and pros alike.

Checking out this phrase, we’ll see that it only uses notes from the pentatonic scale. We’ve got quarter notes and a few eighth notes for some rhythmic variation.

To emphasize the pentatonic sound, we’ll start on the root with a quarter note, playing a couple eighth notes that bring us back to that fifth, jumping up to the root from there, skipping one degree in the scale. Then we get to the third, playing a couple more quarter notes. This helps us embellish the sound, then we add some syncopation at the end, playing straight up the scale and bringing it back to the root at the end.

Master Chromaticism

Our final tip today is to master chromaticism—which is obviously easier said than done. However, you can play between the scale tones really melodically, and this gives you a jazzier sound.

Diving in here, you’ll see we have a bunch of chromaticism to start, but in the rest of the phrase, it’s just straight scale notes—mainly even just chord tones.

So really, the most complex part of this phrase is just the beginning!

We’re starting with a big four-note enclosure—which takes two chromatic notes below and two chromatic notes above to drive us toward our target tone—the seventh of F7. For more about approach notes and enclosures, be sure to check out our 15 Approach Note and Enclosure Exercise blog. If this seems tricky, check out how Chad does it in the video.

After that enclosure, we’re just going to play chord tones going down again into the seventh, then the fifth and the third. We’ll connect with stepwise motion to the fifth of the next chord. We’ll end the phrase on the fifth and the third for a nice snappy ending.

This is another one of our short ii - V - I progressions. While the chromatic enclosure and approach notes made it look a little tough, there are only so many in-between notes. So if you get used to doing approaches and enclosures in all 12 keys, you’ll get used to how they feel and you’ll have them under your fingers, and ready to use.

When you learn a phrase in another key, it goes beyond just pushing the buttons—it helps you really internalize the sound and the concepts, which makes you internalize why that phrase works. This helps you integrate this new language into your own playing and improv.

There’s no magic button to make you better at jazz improvisation, but from a mechanical perspective, the most valuable thing you can do is learn phrases in all 12 keys—which is why so many of our PDF packages have exercises in all the keys.

Happy Shedding!

Thanks for stopping by for another blog—make sure to check out some of our others on playing over ii - V - I progressions, practicing jazz standards, soloing on the blues, and much more.

Don’t forget to check out the video for this topic, along with the PDF package 50 Easy Major Licks so you can get the most out of these concepts. After working through these, you’ll notice it in your playing soon enough!

Comments