STOP learning jazz standards without doing this!

- Jazz Lesson Videos

- Apr 24, 2023

- 9 min read

Let’s cut right to the chase: scales have a bad rap. A lot of beginner and intermediate players do not like scales—when you’re starting out they can be kind of confusing. Maybe you had a very by-the-book music teacher who was obsessed with drilling scales into you, and that kind of turned you off to scales.

There are a bunch of techniques and exercises you can apply to playing standards, but it’s easy to get lost on the the most important thing—keeping the fundamentals of a standard (i.e. the changes) in mind as well as the corresponding scales for each chord. Remember—harmony and melody are two parts of the same thing. You can think of melody as horizontal harmony, or harmony as vertical melody (thinking in reference to sheet music, that is). So if you want to play a melody, it’s important to understand the harmony and vice versa.

But some of this bad rap can come from people using scales ineffectively—maybe you’ve tried playing with scales and felt like you were just pushing buttons trying to find something that sounded good.

Usually as a beginner, you’ll learn that a tune is in F, then spend the entire tune moseying around the F major scale, sometimes hitting some really awesome notes, and other times hitting some less exciting notes. But eventually, you feel like you want to break out and play something else. And if there are chromatic notes or altered chords, you’ll need to break out of that single-scale approach and look more to chord scales, or the diatonic scales that correspond to each chord.

So today we’re going to talk about some of the elements that can make chord scales sound really good. But before we get going, you’ll definitely want to check out our new PDF package called 20 Chord Scale Etudes on Jazz Standards. Chad LB wrote out 20 etudes on standard chord progressions where he only used the chord scales so they could be as melodic and fundamentally sound as possible. That’s up on our website now, along with backing tracks and recordings of Chad playing through the tunes.

Now let’s get playing!

Contents

Making scales work for you

Alright, so our whole point of playing a scale that matches with a chord is actually to embellish the chord. And when you move fluidly from one chord to another, and you’re actually playing scales effectively from one chord to another, by nature it will sound very melodic.

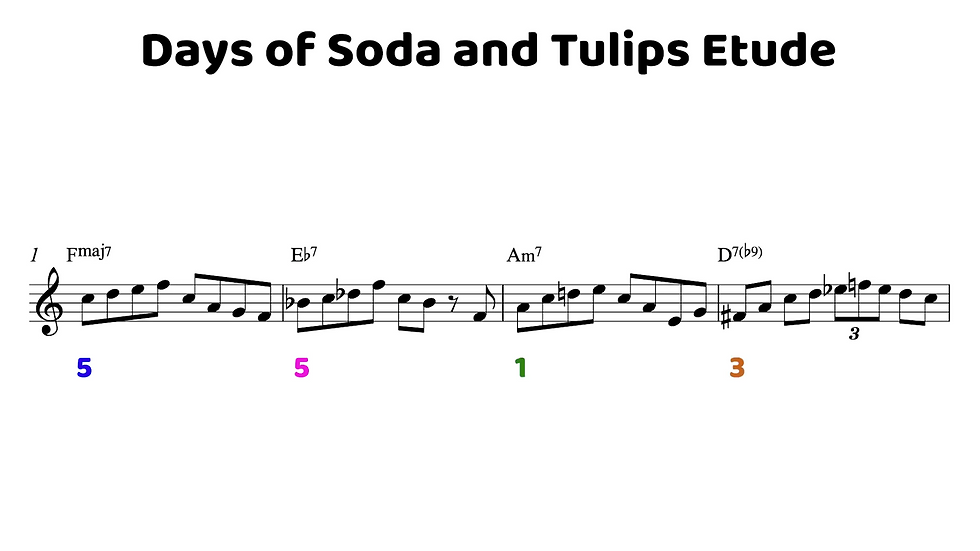

We’re going to check out one of the etudes from our new PDF as a reference point for how you can do this effectively. We’ll start off on our etude “Days of Soda and Tulips.” We’re going to check out the first 16 bars of the etude and listen and analyze it a bit.

So make sure to check out our accompanying YouTube video to get a better feel for how Chad plays it.

What we’re going to do first with every standard is just make sure we know every scale that matches with each chord. Now this gets into some light theory, but stay with us—it’s worth it. And just because you don’t understand the theory doesn’t mean you can’t play along—in fact, that’s the best way to do it, because you’ll start to learn how some of the theory concepts sound. But you’ll see in the PDF that we have a reference chart for each standard, which includes the chord scales for the changes.

For a lot of you, this first bit might be pretty straightforward. But you’ll see that we get into some interesting options as we move through the tune. It’s important to remember that you can play anything you want over any chord—you don’t just need to stick to scale tones or arpeggios. But it’s also important to move with purpose and intention if you want things to sound coherent. Knowing your home base chord and scale relationships will give you a solid foundation to use anytime, or to resolve into if you are playing outside.

Our tune starts on Fmaj7, so that’s pretty easy—that means we’ll play in F major. Next we see an Eb7, which means the home scale of that chord is Eb Mixolydian. But when we have an Eb7 on a tune that’s in F major, that Eb is functioning as a backdoor dominant, or a dominant a whole step below the tonic. Seeing that it’s a backdoor dominant, we could either play regular Mixolydian or we could play what’s called the Lydian Dominant scale—which is a Mixolydian scale with a sharp 4 (or 11, depending on how you look at it).

In measure three we see an Am7, but we have a few options here. We of course have our default m7 scale, which is Dorian. But looking at the placement of this chord in the scale, we see that it’s the iii chord—meaning that its respective tonality is actually from the A Phyrgian scale, which is the same as F major. So we can use either of these options here, the only note is that A Dorian will introduce a natural 6 (in this case F#) versus A Phyrgian, which will retain the flat 6 (F).

Moving into measure four, we see a dominant flat 9 chord. And anytime you have a 7b9 chord, you’re going to have a few options. Chad’s favorites are Phyrgian Dominant and the half-whole diminished scale. Phyrgian Dominant is essentially a Mixolydian scale with a lowered second/ninth and lowered sixth/thirteenth. It’s an awesome choice and is very melodic. But we’re going to choose the half-whole diminished scale—which is exactly what it sounds like. From the root, you’ll move up a half step, then a whole step, then a half step, etc. until you return to the root.

This option is going to give you a natural 6, as opposed to the flat 6 from the Phyrgian Dominant.

Then we come to a Gm7, where we have two different options—we can use Dorian again, or we can use the melodic minor, which is where that F# is coming from in the melody line. It’s important to note that in jazz, the melodic minor scale is a bit different than the classical melodic minor, since that one changes based on whether you’re ascending or descending the scale. In jazz, it’s easier—it’s all the same, whether you’re ascending or descending—it’s the same as Dorian, just with a raised seventh.

From there, we’re back to the Eb7, our backdoor dominant. What we’ll do here is just the regular Mixolydian, but again, we could raise that fourth in the Mixolydian, too, for the Lydian Dominant sound.

Here we get into a iii chord again, so we can either do Dorian or Phrygian, but it doesn’t really matter in this case since we only play a few notes to break up the rhythm anyway.

Then we’re moving into a Dm chord, which is the vi of F, so you can use the natural minor or Dorian if you want.

Again, if you didn’t understand all the theory behind this, that’s totally ok. What’s important is practicing these scales and seeing if you can get through the standard fluently, like what we have here.

Continuing on, we’ve got a Gm, which is the ii. Then it’s over to Gm7/F, which is just changing the bass note to walk down to the next harmonic device. And you’ll see we have a nice thing going, starting with a triplet to mix up the rhythm a bit, we got up from the seven to the root on the triplet, back down and arpeggio back to the root, where we step up diatonically into the second, which is going to be that A on the Gm7/F, and we arpeggiate.

Again, the Bb, D, F, and A is just an arpeggio going up the 3, 5, 7, and 9, and we step down diatonically into the root of the next chord, which is an Eø7. The E half-diminished seven becomes a minor ii-V of vi, which is how we end up on vi, or Dm, in the next measure. Then the G7 is a secondary dominant, or what you might call a V/V (five of five) in this case. Basically, it’s a dominant ii chord, which acts as the dominant for the dominant chord, where G resolves to the fifth, C, and C resolves to the root, F. In this case, the II7 goes to ii to drag out the resolution, but then it moves to V and back to I.

That was a lot of harmony going on—but what you need to realize is that as you practice the scales that match with each chord and you try to get fluidly from measure to measure, you’re going to start to hear and understand that harmony better.

Some tips for making chord scales better

One thing to notice is that we’re landing on chord tones all the way through.

So if you look at that first measure, we’re starting on the fifth of Fmaj7 (or C), then we played the fifth of Eb7 (Bb), then we played the root of Am, the third of D7b9 (F#), the third of Gm7, a few measures later we change to an Eb7 and land on the third, and then the fifth in the next bar. We’ve got a root on the Am. Then for the first time we play something other than our 1, 3, 5, and 7 on the Dm7 shape. This is kind of a stock, nice melodic shape, where we start on the second, then arpeggiate up to the ninth (since the second and ninth are the same note). Then again we’ve got a common melodic shape with 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 1.

Point being, we’ve got about eight measures straight of just chord tones on the downbeat of each measure. So that’s a really nice melodic way to play through standards.

This is the first of three elements you can use to make your chord scales sound better. The second one is voice leading. You see as we go from measure three to four and four to five, we have some good examples of effective voice leading. We wrap around the note when we go from Am7 to D7b9—we’ve got the E, the G, landing on the F#. And from measure four to five, we’re stepping down into the note.

Our third element is thinking about the rhythm. One thing that isn’t talked about enough in jazz education is that the rhythm and playing with rhythmic integrity is really important when it comes to playing melodically. If your rhythmic placement is off and your integrity is off, then the notes aren’t going to end up feeling good either.

One thing you can do is think about rhyming your phrases with similar rhythms or even building off of a rhythmic motif.

Building on rhythm

We’re going to dive a bit more into rhythm in in this next etude, which we’ll call “All the Things You Could Be.”

You’ll see the same idea where we’ll use the notes that match the scale of each chord, but we’re going to have more rhythmic action.

Looking at our first four bars, you’ll see that by having rhythmic similarity in the two phrases—with a rest on beat one of the second bar of each phrase and then the “and” of one being essentially the end of the phrase, this just creates the feeling of rhyming, and then we do an exact rhythmic rhyme.

In the fifth and sixth bars, we’ve got the same exact rhythm with just a variation on the second phrase. You’ll see this rhythmic interplay in the lines ends up being a theme through this entire etude.

So you’ll see the rhythmic direction is a really key factor when it comes to playing interesting phrases using just the scale notes through the standard. Again, the fundamentals are a really helpful thing to tackle on standards. It’s where you should start, and it’s also where you should finish when you’re learning a tune. You’ll never outgrow this concept, no matter what level you’re at—both for easier tunes like Autumn Leaves and more complex tunes like Stella By Starlight, where you have really complex changes. Both of the standards we just mentioned are covered as etudes in our PDF ebook.

Play us out!

We thought we’d cover one more before we go—and this etude is based on the Stella changes, but we’ll call this “Sarah By Moonlight.” Check out how Chad plays through it in our accompanying video.

With this tune, you’ll see a really complex set of chord changes, and sticking with the scale notes melodically is a really simple way to get through these changes cleanly.

The striking thing about this tune is that it’s in Bb, but we don’t even get a Bb chord until measure nine. But when we’ve got harmony like this, it gets really intricate. That’s why it’s important to have a strong handle on your scales and be able to use them melodically to get through a tune in a way that sounds nice.

That’s it for this one, guys, see you next time!

Comments